I have a silly dream of seeing graphical Linux/FOSS programs running portably on any browser-based system outside of app store constraints. Two of my weekend side projects are working in this direction: an x86 emulator core to load and run ELF binaries, and better emscripten cross-compilation support for the GTK+ stack.

Emulation ideas

An x86 emulator written in WebAssembly could run pre-built Linux binaries, meaning in theory you could make an automated packager for anything in a popular software repository.

But even if all the hard work of making a process-level emulator work, and hooking up the Linux-level libraries to emulated devices for i/o and rendering, there are some big performance implications, and you’re probably also bundling lots of library code you don’t need at runtime.

Instruction decoding and dispatch will be slow, much slower than native. And it looks pretty complex to do JIT-ing of traces. While I think it could be made to work in principle, I don’t think it’ll ever give a satisfactory user experience.

Cross-compilation

Since we’ve got the source of Linux/FOSS programs by definition, cross-compiling them directly to WebAssembly will give far better performance!

In theory even something from the GNOME stack would work, given an emscripten-specific gdk backend rendering to a WebGL canvas just like games use SDL2 or similar to wrap i/o.

But long before we can get to that, there are low-level library dependencies.

Let’s start with glib, which implements a bunch of runtime functions and the GObject type system, used throughout the stack.

Glib needs libffi, a library for calling functions with at-runtime call signatures and creating closure functions which enclose a state variable around a callback.

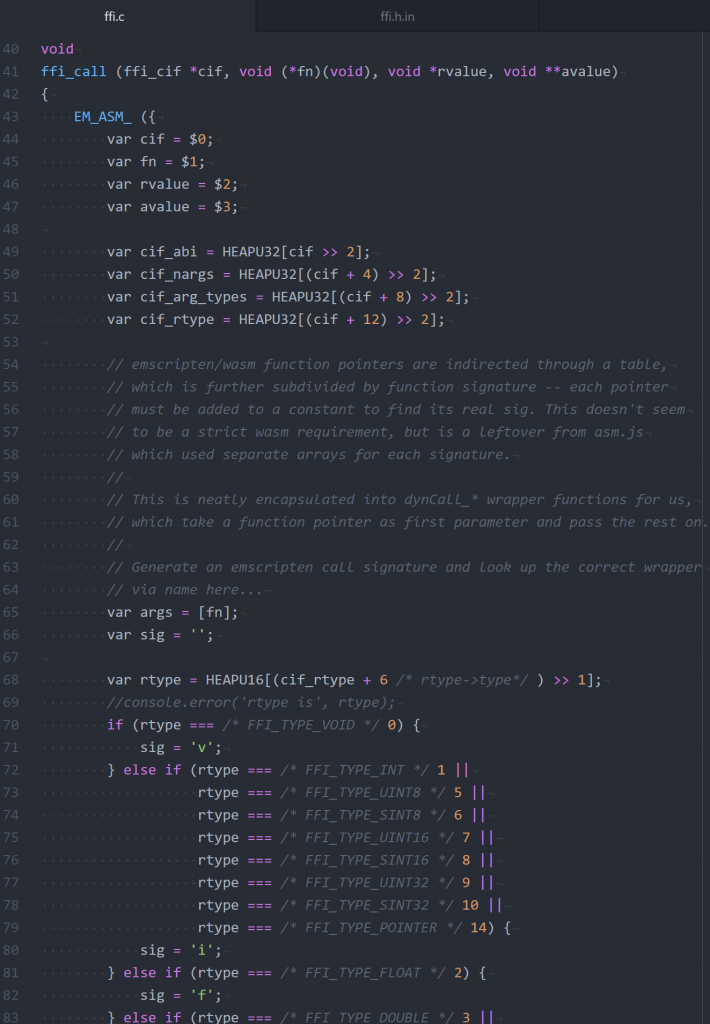

In other words, libffi needs to do things that you cannot do in standard C, because it needs system-specific information about how function arguments and return values are transferred (part of the ABI, application binary interface). And to top it off, in many cases (emscripten included) you still can’t do it in C, because asm.js and WebAssembly provide no way to make a call with an arbitrary argument list. So, like a new binary platform, libffi must be ported…

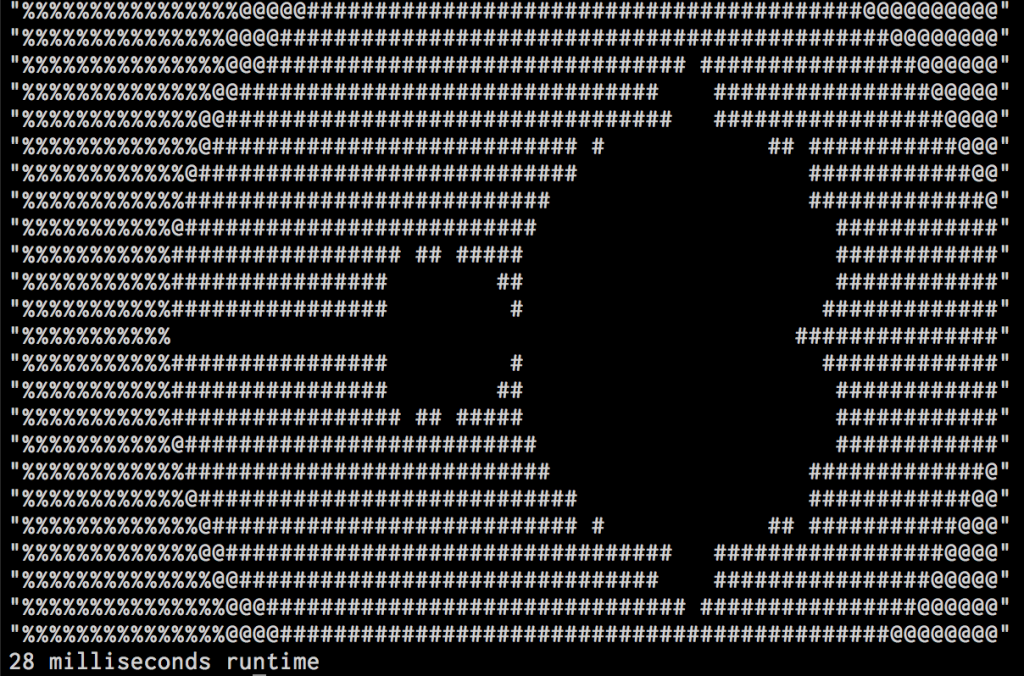

It seems to be doable by bumping up to JavaScript, where you can construct an array of mixed-type arguments and use Function.prototype.apply to call the target function. Using an EM_ASM_ block in my shiny new wasm32/ffi.c I was able to write a JavaScript implementation of the guts of ffi_call which works for int, float, and double parameters (still have to implement 64-bit ints and structs).

The second part of libffi is the closure creation API, which I think requires creating a closure function in the JavaScript side, inserting it into the module’s function tables, and then returning the appropriate index as its address. This should be doable, but I haven’t started yet.

Emscripten function pointers

There are two output targets for the emscripten compiler: asm.js JavaScript and WebAssembly. They have similar capabilities and the wrapper JS is much the same in both, but there are some differences in implementation and internals as well as the code format.

One is in function tables for indirect calls. In both cases, the low-level asm.js/WASM code can’t store the actual pointer address of a function, so they use an index into a table of functions. Any function whose address is taken at compile time is added to the table, and its index used as the address. Then, when an indirect call through a “function pointer” is made, the pointer is used as the index into the function table, and an actual function call is made on it. Voila!

In asm.js, there are lots of Weird Things done about type consistency to make the JavaScript compilers fast. One is that the JS compiler gets confused if you have an array of functions that _contain different signatures_, making indirect calls run through slower paths in final compiled code. So for each distinct function signature (“returns void” or “returns int, called with float32” etc) there was a separate array. This also means that function pointers have meaning only with their exact function signature — if you take a pointer to a function with a parameter and call it without one, it could end up calling an entirely different function at runtime because that index has a different meaning in that signature!

In WebAssembly, this is handled differently. Signatures are encoded at the call site in the call_indirect opcode, so no type inference needs to be done.

But.

At least currently, the asm.js-style table separation is still being used, with the multiple tables encoded into the single WebAssembly table with a compile-time-known constant offset.

In both cases, the JS side can do indirect calls by calculating the signature string (“vf” for “void return, float32 arg” etc) and calling the appropriate “dynCall_vf” etc method, passing first the pointer and then the rest of the argument list. On asm.js this will look up in the tables directly; on WASM it’ll apply the index.

(etc)

(etc)

It’s possible that emscripten will change the WASM mode to use a single array without the constant offset indirection. This will simplify lookups, and I think make it easier to add more functions at runtime.

Because you see, if you want to add a callback at runtime, like libffi’s closure API wants to, then you need to add another entry to that table. And in asm.js the table sizes are fixed for asm.js validation rules, and in WASM current mode the sub-tables are definitely fixed at compile time, since those constant offsets are used throughout.

So currently there’s an option you can use at build time to reserve room for runtime function pointers, I think I’ll have to use it, but that only reserves *fixed space* of a given number of pointers.

Next

Coming up next time: int64 and struct in the emscripten ABI, and does the closure API work as expected?